🏫💻 Homework vs Robots: Are Our Schools and Universities Ready for AI?

This first semester has been a bit strange for schools and universities.

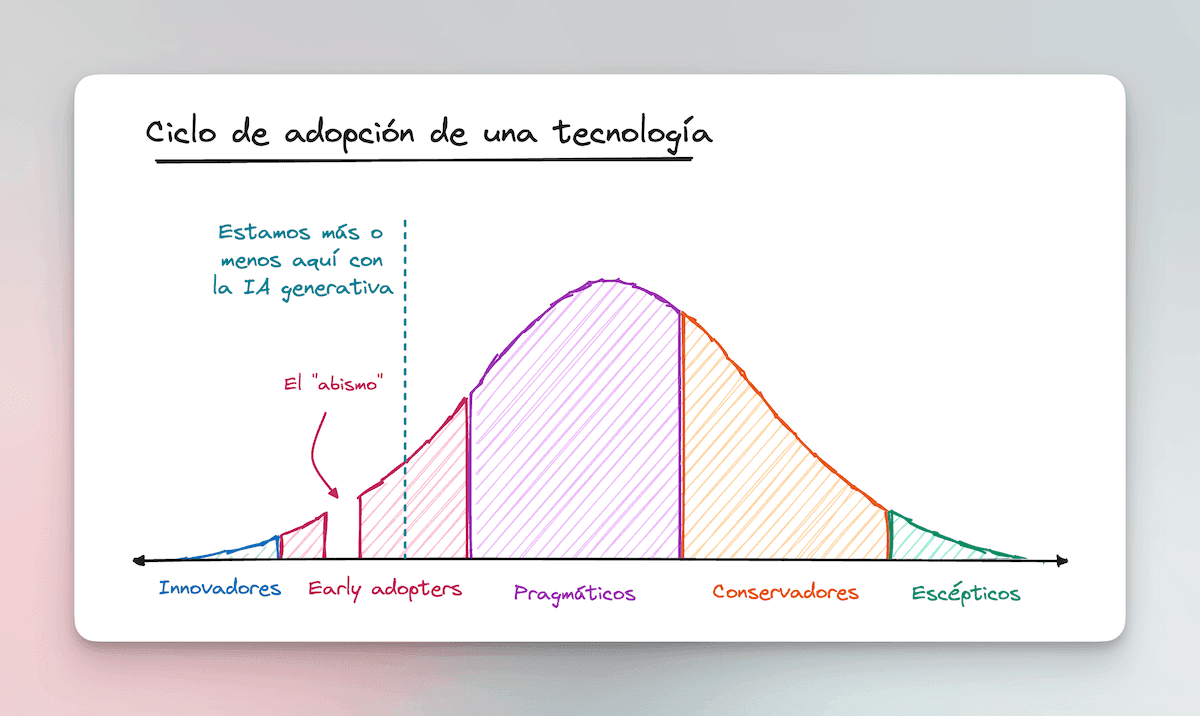

To understand it, let’s first look at the standard adoption cycle that all new technology goes through:

It is born with the “innovators.” These are the people who create the technology and are the first to experiment with it (less than 3% of the population).

Then come the “Early Adopters,” people from the general public who enjoy trying new technologies. If you’re reading this newsletter, we’re probably in this group (less than 17% of the population).

The technology has to pass the “chasm” test, where most new products die due to lack of traction.

If that happens, it then continues its adoption cycle toward the more conservative groups (the remaining 80% of the population).

With generative AI, it’s safe to say we’ve already crossed the chasm. According to

, 14% of adults have used ChatGPT at least once.

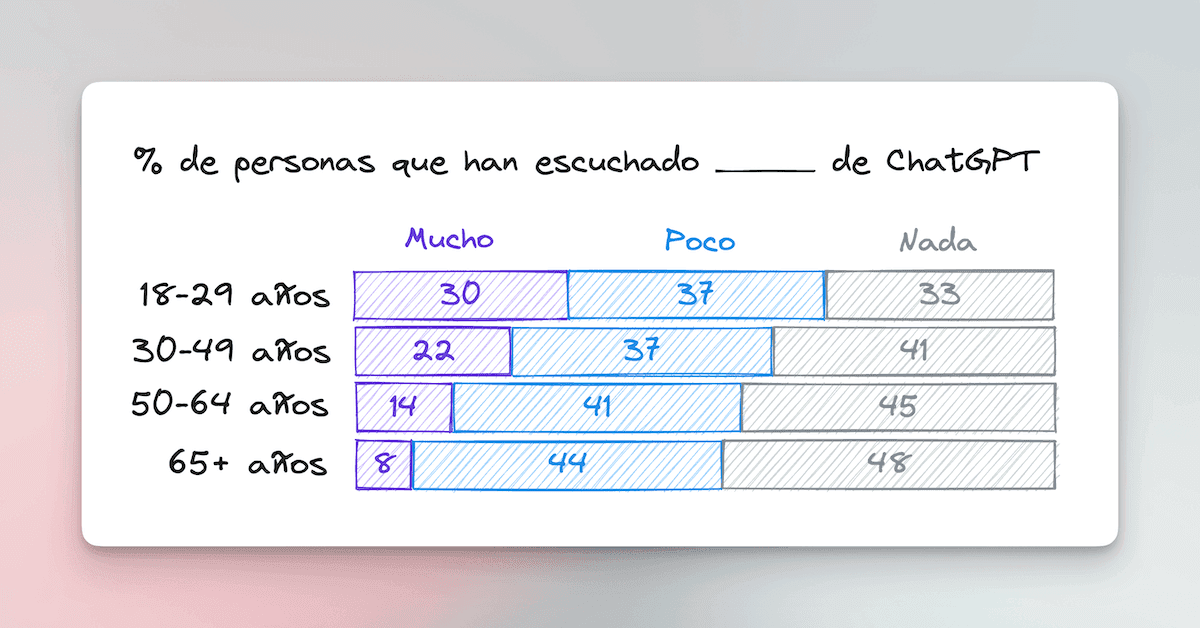

The problem in education is that adoption is different between teachers and students.

We don’t have adoption data for those under 18, but I have no doubt it follows the trend of the graph: younger generations know and use ChatGPT more than older ones.

This has raised alarms in several schools and universities, where students are already using ChatGPT to cheat, while most teachers are just getting to know the technology, or some have never even heard of it (I can only imagine the surprise of the latter when Pedro shows up with an essay written as if it were Shakespeare).

Let’s review some of the “classic” tasks that a teacher assigns for homework.

The Essay

It is one of the most commonly used educational tools. It serves to teach students to write, think, and reflect. It’s a good way to empty “what a student is thinking” onto paper for the teacher to evaluate later.

But essays are also the specialty of models like ChatGPT.

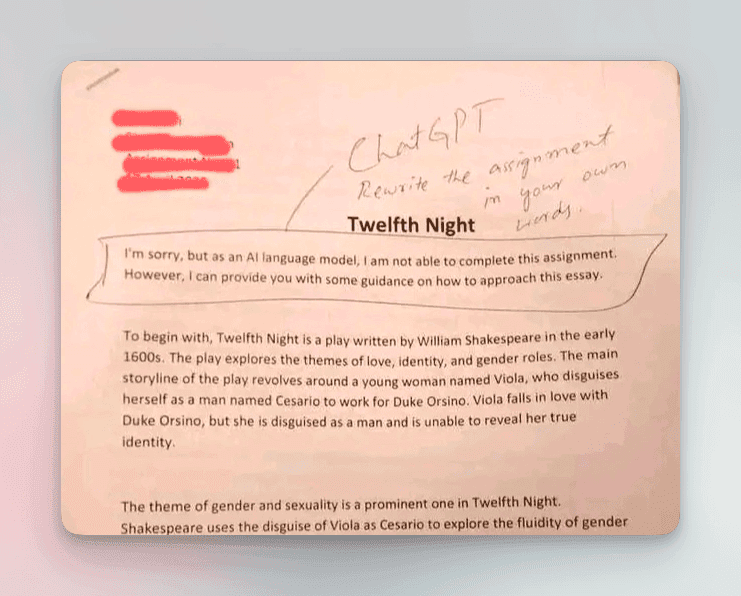

Unless you’re the student in the photo below, you can generate credible and well-structured essays with very little effort.

An essay in English that starts with “I’m sorry, but as an AI language model, I cannot do your homework…” The student probably copied and pasted what ChatGPT delivered without even looking at it 🤦♂️.

The three biggest problems that essays written by ChatGPT had are now disappearing:

Originality: if you use the free version of ChatGPT, you’ll notice that the essays it delivers are very generic and feel “robotic.” But the new GPT-4 model, which can be accessed in the paid version (or for free in Microsoft’s browser), produces much more convincing and better-written texts.

Detection: there are some tools that seek to detect when an essay has been written by AI. But they are not very good at it. In this study, where essays written by humans and by ChatGPT were evaluated, more than half of the essays were marked as "false positives" (they were flagged as generated by AI when they were written by students).

Hallucination: the Achilles' heel of ChatGPT. If you ask for a quote or a reference, it is very likely to make it up. But the new models have the ability to connect to the internet, which drastically reduces the possibility of them inventing something incorrect.

So, if students can generate perfect essays with little effort, what can be done?

The answer is binary.

If you want to evaluate how a student writes, then your best option is to return to the analog world: handwritten essays and live presentations.

But generally, when a teacher assigns an essay, what they seek is to evaluate other types of cognitive skills: problem-solving, developing opinions, understanding a topic, and synthesis ability.

Writing is a means, not an end.

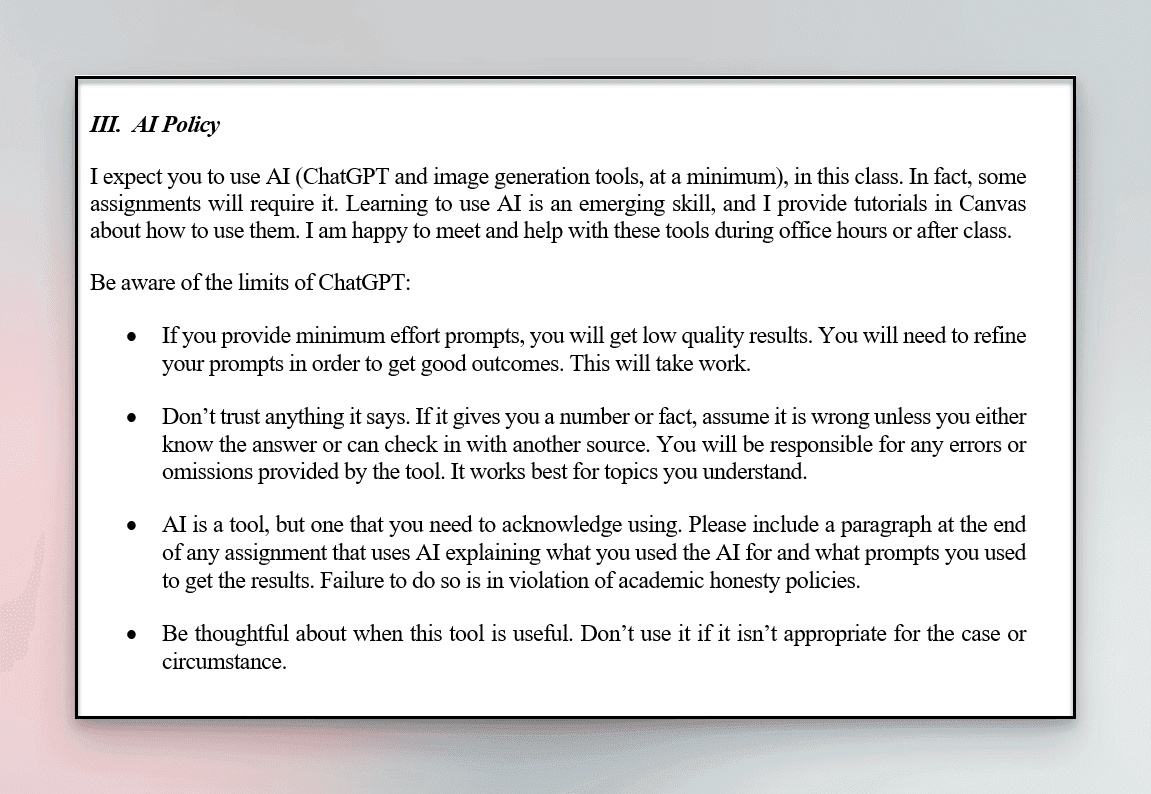

Therefore, if your tasks or projects seek to evaluate something beyond writing, and do not exist in the analog world, then the best approach is to assume that the student has access to AI and raise the bar. Even go a step further and, like this university professor, make the use of AI mandatory in class for some projects.

The AI usage policy of the professor cited above. It states that for some tasks, the use of AI will be mandatory, provides some usage recommendations, and stipulates that students must comment on when and how they used AI.

Reading Comprehension

This is another common form of assessment in schools and universities. In its purest form, it seeks to review whether a student understands what they have read, through book reports, tests with questions, or essays.

But ChatGPT and its cousins, Claude from Anthropic and Bing Chat from Microsoft, are very good at reading, summarizing, and analyzing text.

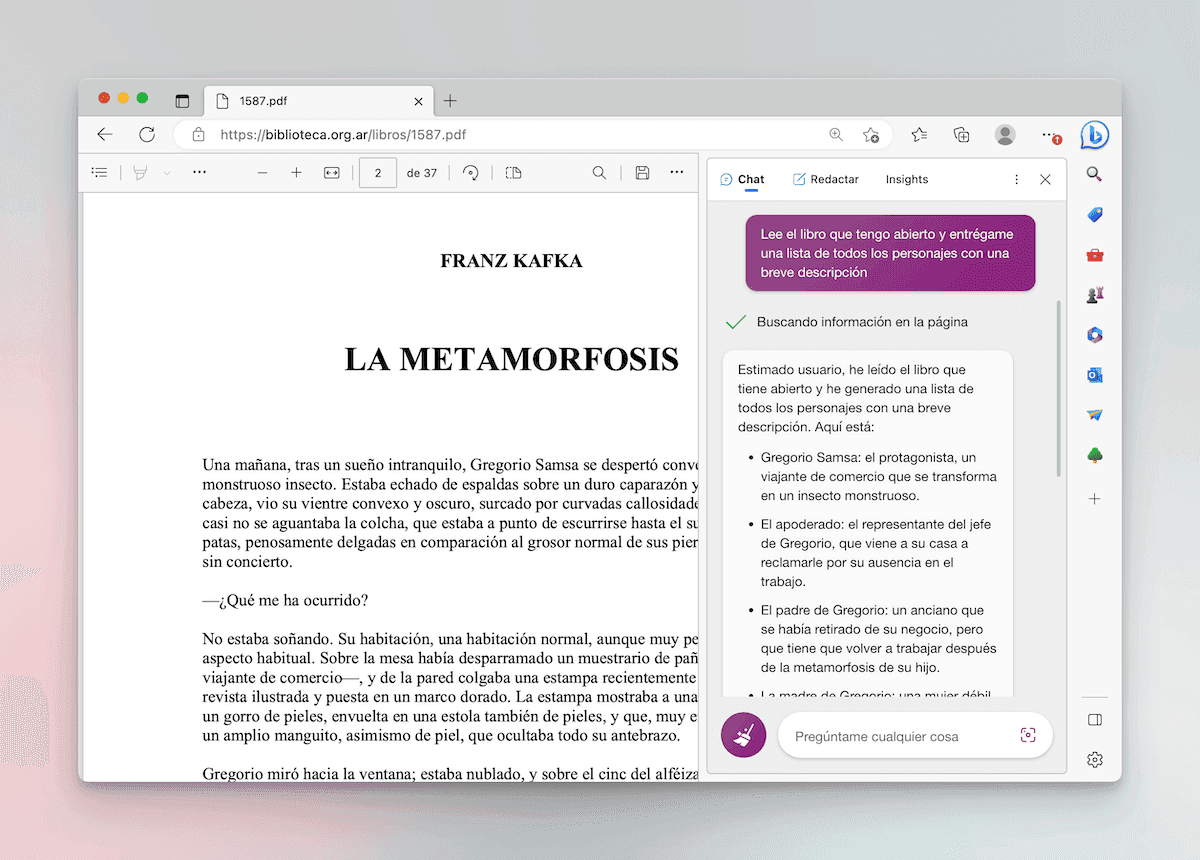

Look at this example where I passed a 37-page PDF to Bing Chat and asked about the characters in the story.

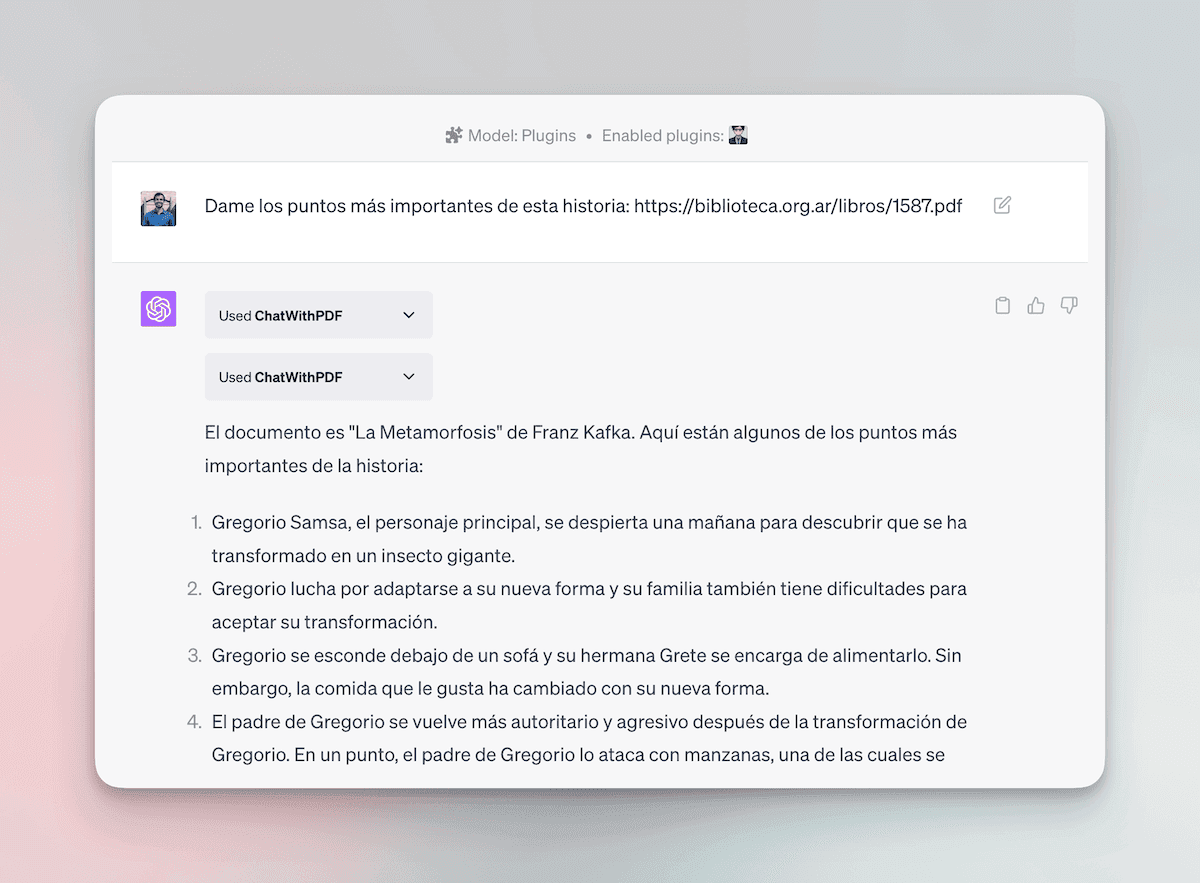

If you have the paid version of ChatGPT, you can do the same using the “ChatWithPDF” plugin.

A third alternative is to copy and paste the book into Claude-100k, which is a model where you can write prompts of 75,000 words.

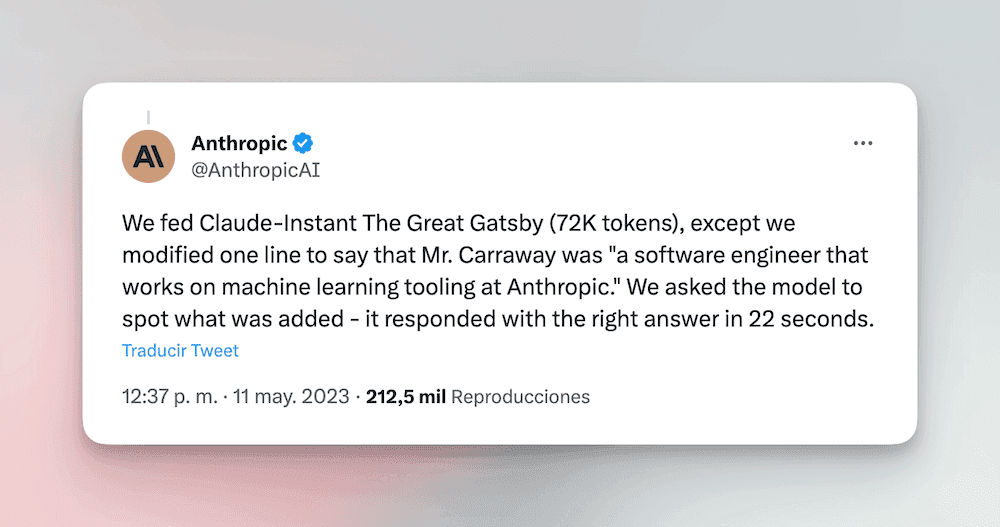

They copied and pasted The Great Gatsby but changed one line from the entire book. The model took 22 seconds to find the error.

What can be done in a world where students have a “Rincón del Vago” with steroids in their pockets?

...(about 43 lines omitted)...

AI is not going to disappear. If for some strange reason all advances in artificial intelligence were to stop, the technology has already advanced enough to destabilize our educational system. And the reality is that AI is not going to stop. On the contrary, it is advancing at a speed that is hard to keep up with.

AI will be impossible to detect. It’s almost there today. As new models come out, it will become increasingly difficult. Therefore, opposing its adoption in education through prohibitions is a short-sighted and potentially unfair strategy (thinking about the students who may benefit from it).

Sooner or later, students will want to know why they are doing tasks that feel obsolete. It’s like if a math teacher assigned homework for multiplication like 45,315 x 668,512. The student will look at the assignment, sigh in disappointment, pull out their calculator, and do it in seconds.

In the school world, parents will start asking the same questions. And they will start pressuring schools with questions like: What is your AI usage policy in classes? How are you preparing my child for a world where the use of AI in work will be as common or more so than today?

Many times, the impact that the calculator had on education in the 70s is used as an example. And it has some parallels that sound familiar: 72% of teachers opposed its use in schools, parents thought their children would become dependent on technology and lose basic math skills, and society as a whole thought it was a tool that increased inequality (because it was initially very expensive).

It took 20 years for the calculator to go from enemy to being part of the national curriculum.

20 years.

And it wasn’t so painful because its adoption was also slow: its high price meant that only some students had access to them.

But here is where the calculator example leaves the similarities with AI.

We don’t have 20 years.

When teachers return to class after the winter break, they will face students who have a “homework-solving machine” in their pockets.

And they will have two options. Start using it as an ally today or wait 20 years.