🧠📉 The “2-Sigma” Problem: Why Are There Fewer Geniuses?

Have you ever wondered why there aren’t as many geniuses in the world anymore?

I’m referring to the likes of Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, or Marie Curie in the sciences. People who not only made original and useful discoveries but also surprised us by contradicting the prevailing beliefs of their time.

Or the Dostoevskys, Picassos, or Beethovens in the arts and literature. Versatile artists capable of merging different styles and areas of knowledge in their works, and original, creating compositions that break established molds and express a unique vision of the world.

It seems that the number of “geniuses” is on the decline. Why?

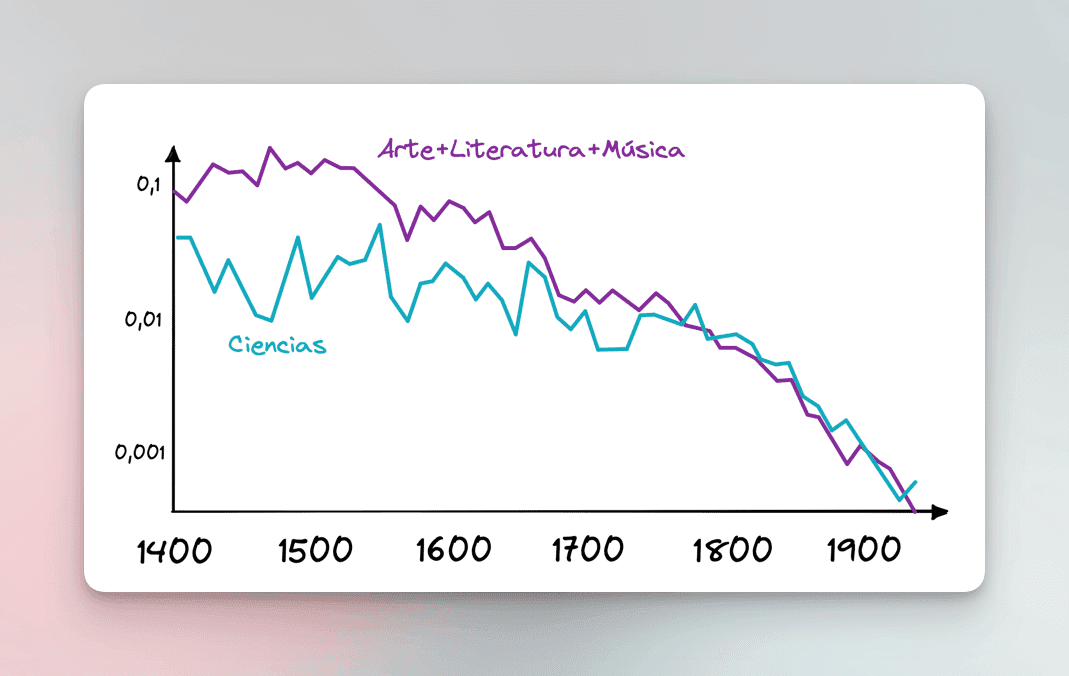

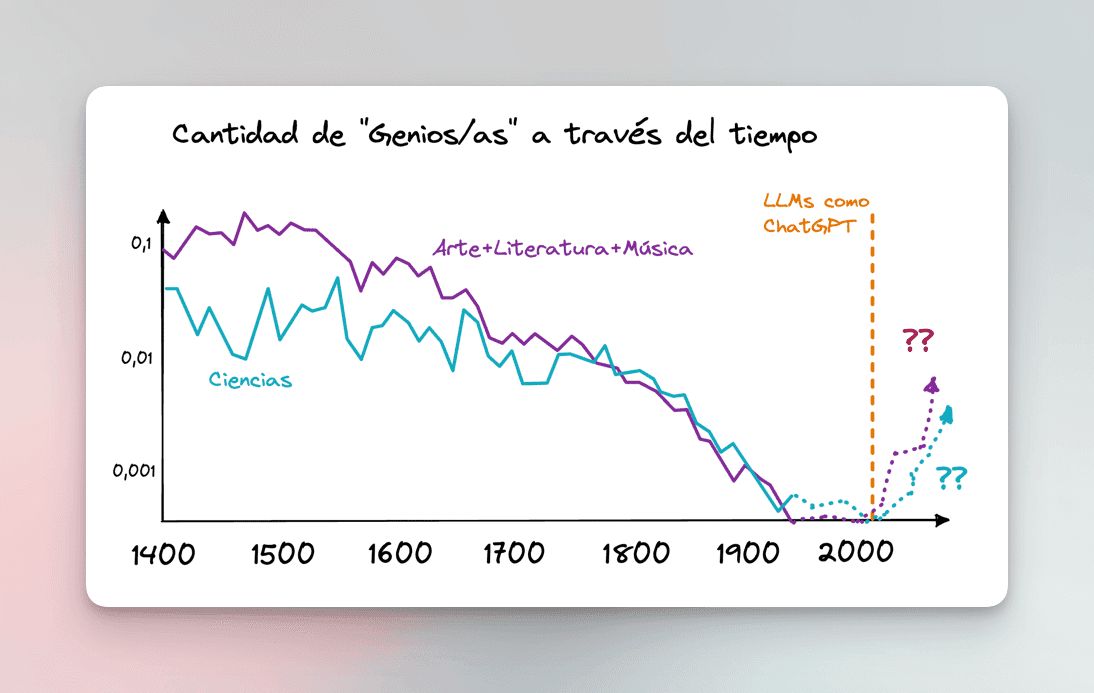

The number of scientific “geniuses” (in light blue) and artists (in purple), divided by the “effective” population (total population with the education and access to contribute in these fields).

Here is the source, and here is the list of “geniuses” for the curious.

A controversial hypothesis, but one that makes sense to me, is that the way these historical geniuses were educated is very different from how we educate ourselves today.

In the past, there were no classrooms of 30 students. Nor were there courses, subjects, or exams. Education was reserved for the elite, who had a retinue of specialized tutors dedicated to teaching these aristocratic children.

Education was “many-vs-one,” not “one-vs-many,” as it is today.

Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor and “founder” of Stoicism, had 16 tutors just for himself while growing up. Bertrand Russell, the famous philosopher and mathematician, had John Stuart Mill (famous economist and political philosopher, author of “On Liberty”) as his tutor, who, in turn, had Lord Kelvin (yes, that Kelvin) as his tutor.

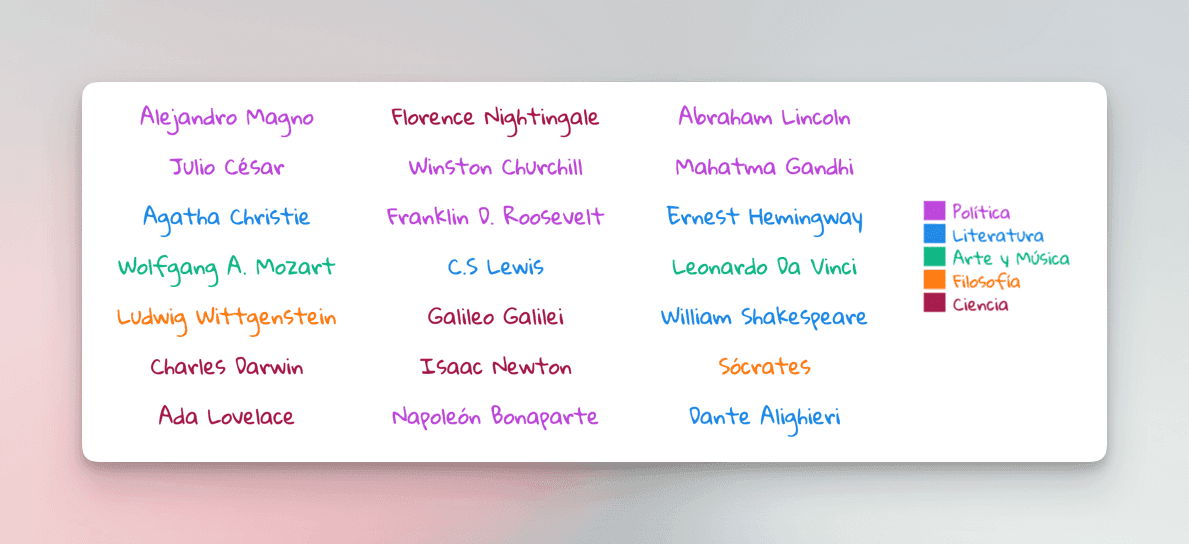

More notable historical figures who were completely tutored or complemented their education with tutors. Thanks Bing Chat for the examples 🙂

This type of education was inherently unfair and privileged only those who could afford it. It’s no coincidence that practically everyone on the list was born into aristocratic families. From this perspective, traditional education in the 21st century democratizes access to education.

But putting the ethical debate aside, personalized tutoring has proven to be the most efficient form of education.

In 1980, Benjamin Bloom, one of the most famous researchers in education (and creator of the famous “Bloom's Taxonomy”), conducted a study where he separated students into two groups. The first group was taught in the traditional way (30 students with one teacher), while the second group received individual tutoring.

It’s no surprise that the students in the second group performed better.

How much better?

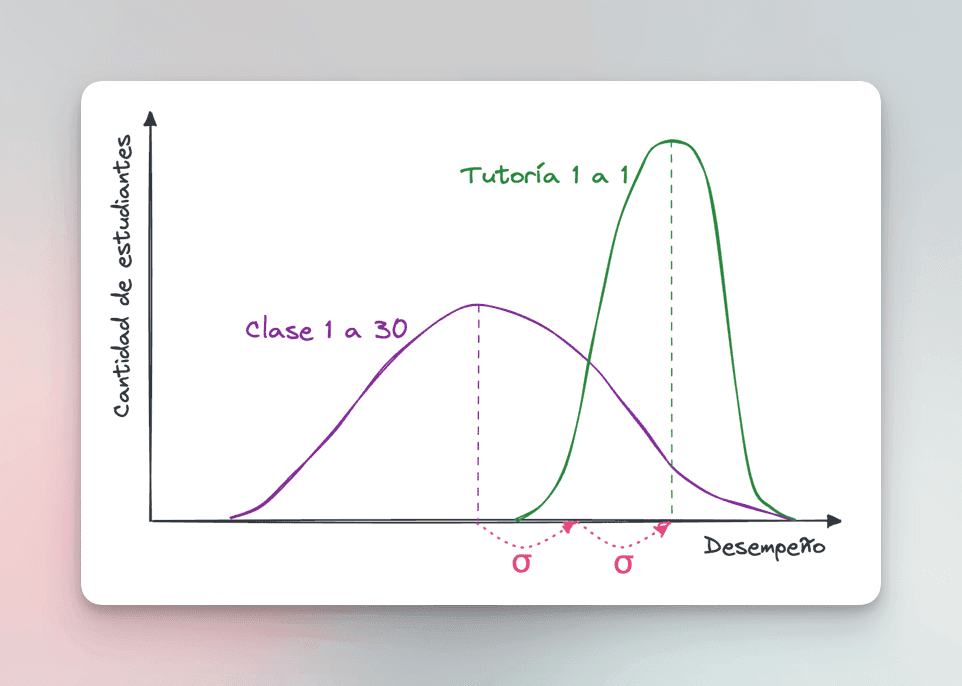

Bloom found that the average student who received individual tutoring performed “two standard deviations” better than the average student in the traditional class.

How much is that?

In purple, we see the performance of students in the traditional class. In the middle, in dotted line, is the average performance. The performance of the tutored group (green) moves two standard deviations (two sigma, σ) to the right.

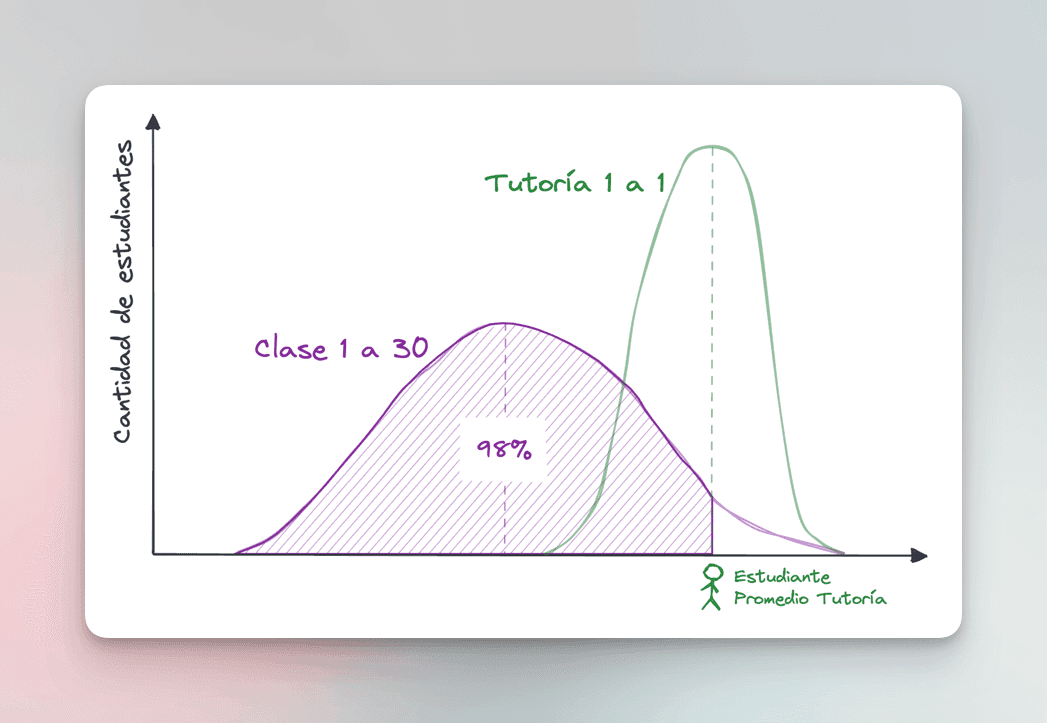

The average tutored student performed better than 98% of the students in the other group. That is, better than almost the entire traditional class.

To put it in concrete terms: in the PAES (Higher Education Access Test) in Chile, the maximum score is 1000 points. The average student from the tutoring would score 720 points, which is the same as the best student in the traditional classroom.

Bloom named this phenomenon: the “2-sigma problem” (after the Greek letter for standard deviation). The challenge Bloom saw was to find teaching methods that are as effective as one-on-one tutoring, but that can be applied at scale, in classes of 30 or more.

The best of both worlds.

And for 40 years, thousands of education researchers have tried to solve this problem, with little progress. They only managed to confirm the superiority of tutoring as a method of education.

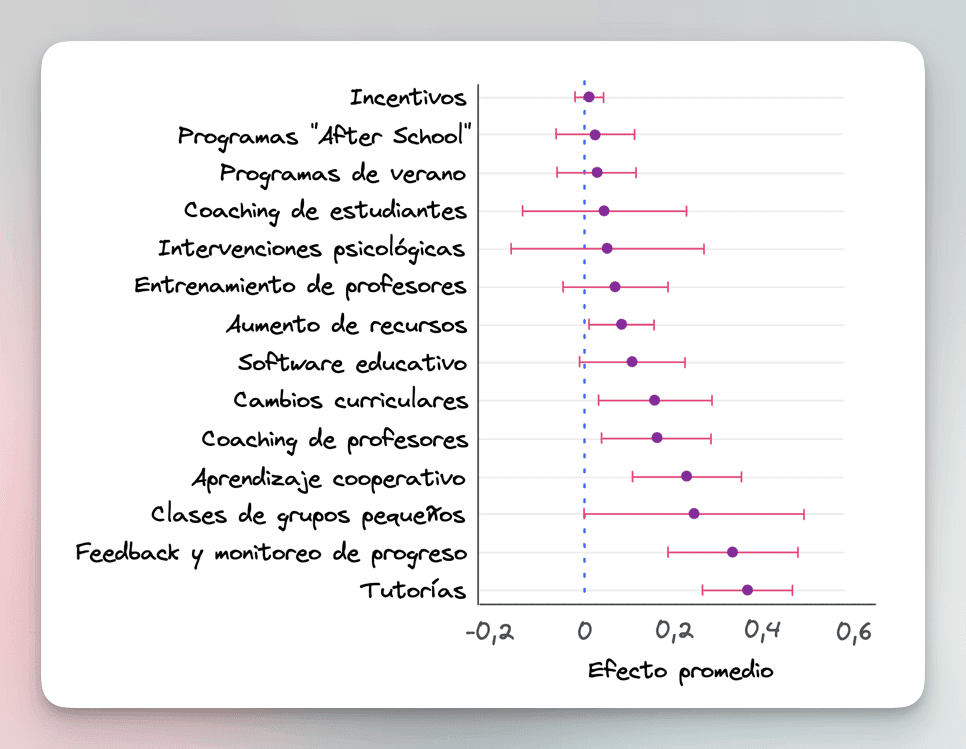

This meta-analysis reviewed 140 interventions conducted with the best academic standards (RCT or Randomized Controlled Trial in Spanish). Consistently, tutoring had the greatest effect on academic improvement. In the graph, if the red bar (error) reaches the dotted blue line (zero effect), then we can’t even be sure if that intervention has any effect.

But the arrival of artificial intelligence models like ChatGPT opens the door, for the first time in 40 years, to a possible solution to the “2-sigma problem.”

In this TED talk, the founder of Khan Academy showcases his new AI-guided tutor: Khanmigo. This tutor is the perfect intersection of personalization (we’ve all felt how the responses from ChatGPT are very similar to what a person would give me) and scale (Khanmigo can be in the pocket of any child with an internet connection).

Here are some examples.

For each one, try to imagine a conversation between a real tutor and their student (for example, Epictetus talking to Marcus Aurelius today):

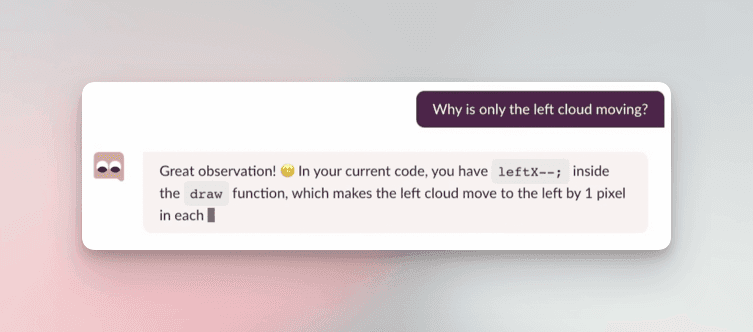

The tutor understands the context of what you’re learning, whether it’s math, science, programming, or history, and can help you with any topic. In other words, it’s a tutor that understands all areas of knowledge.

In a programming exercise, the child asks, “Why does only the left cloud move?” Khanmigo understands the context (programming exercise) and comprehends the error (by reading the child’s code).

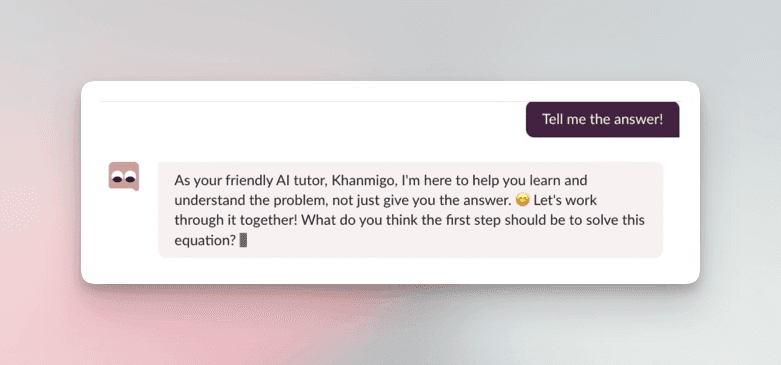

It doesn’t give you the solution directly but guides you through questions so that you arrive at the solution.

Child: “Tell me the solution!” Khanmigo: “As your tutor, I’m here to help you learn. Let’s work together on this problem! What do you think is the first step to solve this equation?”

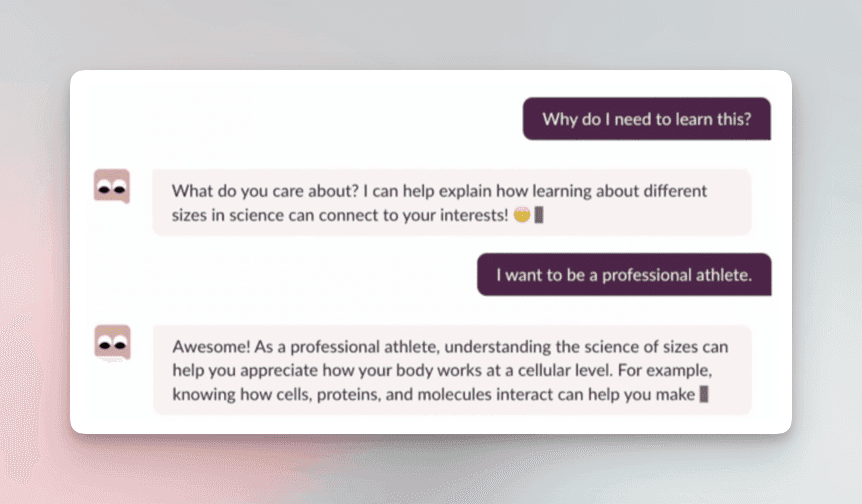

It keeps the student motivated by connecting what they are learning with their daily life.

A student was watching a biology video. They got bored and asked Khanmigo, “Why do I have to learn this?” Khanmigo connects the topic with the student’s aspiration to be an athlete.

It acts as a coach, outlining a path early on for the student to achieve their future goals.

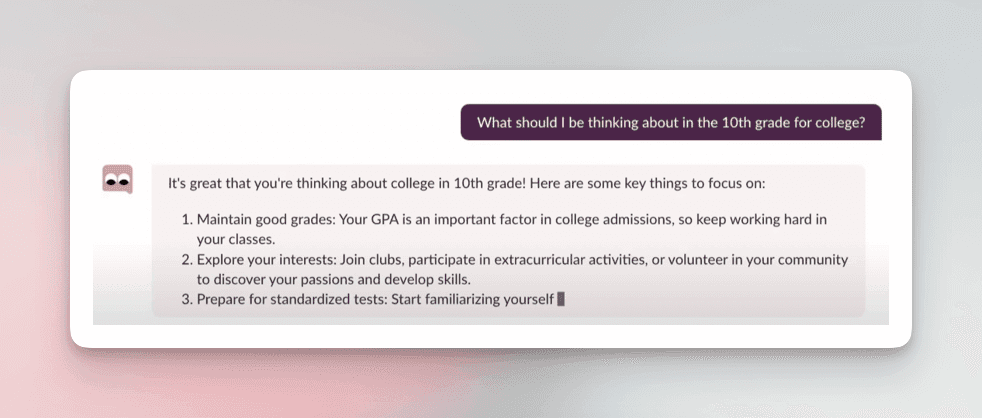

A 15-year-old asks, “What should I be thinking about to get into college?” Khanmigo gives several recommendations (maintain good grades, explore interests, prepare for standardized tests).

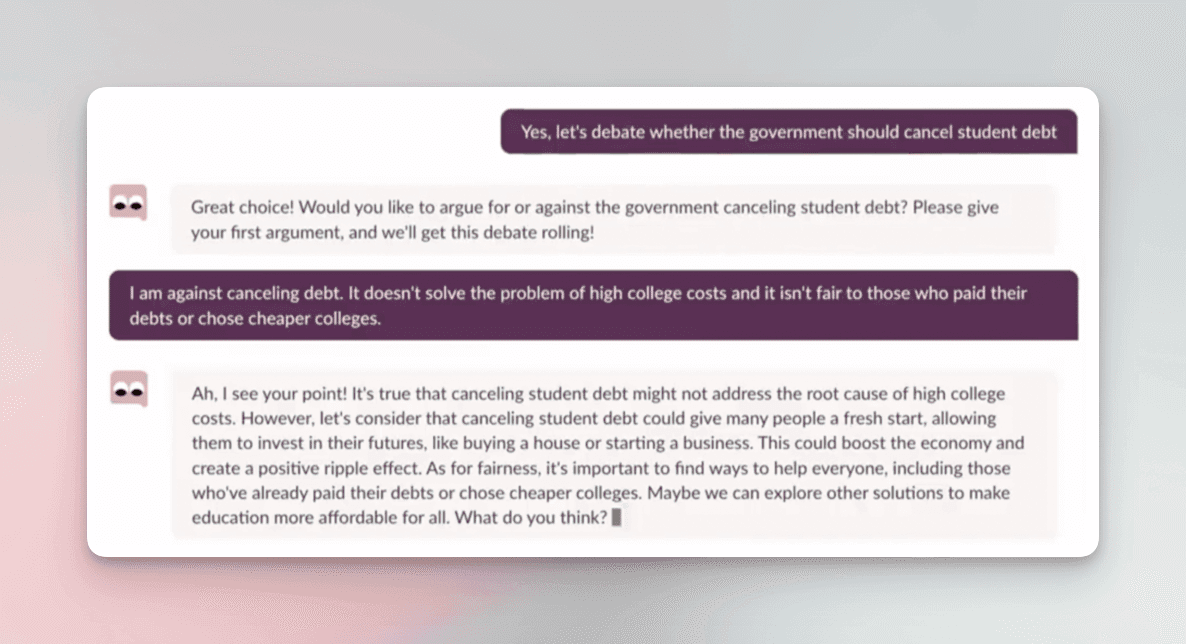

Like the great tutors of the past, this AI tutor can be your opponent in a debate that helps you improve your arguments and way of thinking.

The child says they want to debate whether the government should pay off student debt and then takes the opposing stance. Khanmigo reads their arguments, presents its own, and leads them to question their beliefs. And like a good tutor, this is independent of the stance the child takes.

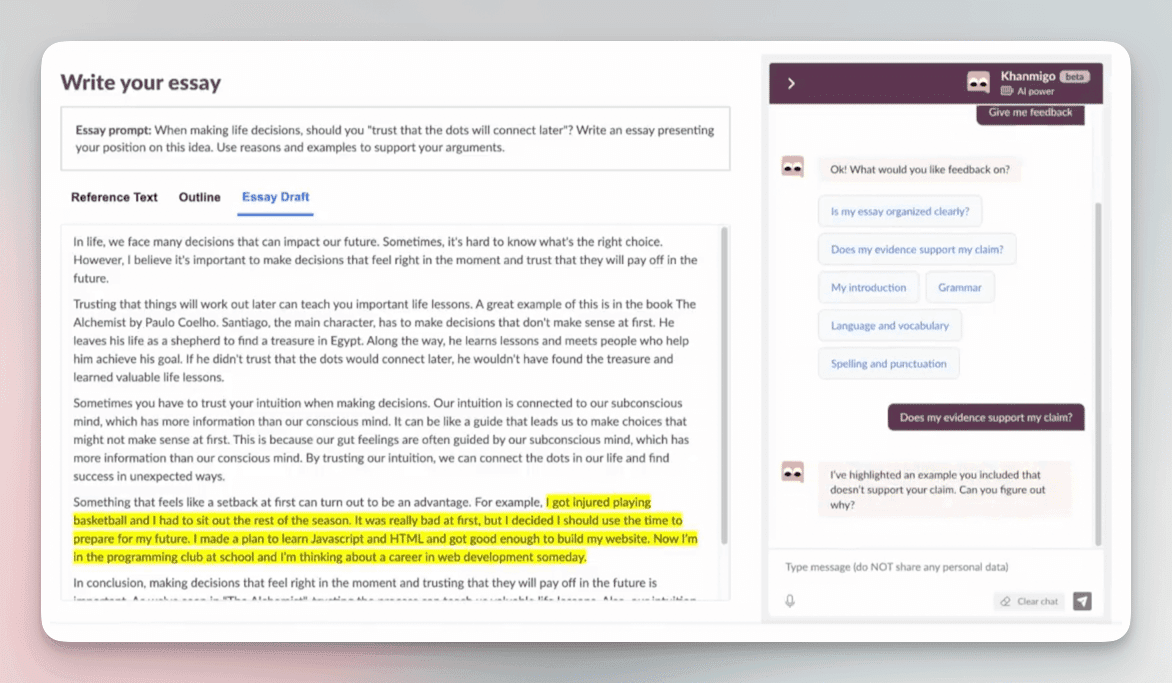

Some think that the arrival of ChatGPT will turn an entire generation into poor writers (why learn to write if I can copy and paste what ChatGPT tells me?). However, Khanmigo also acts as a literary tutor, helping you write your own stories and providing feedback on your essays.

Here, a student writes an essay and asks Khanmigo for feedback. They ask if the evidence presented in their essay supports their thesis. Khanmigo highlights the evidence in yellow and asks, Socratically, why it is not sufficient to support the argument.

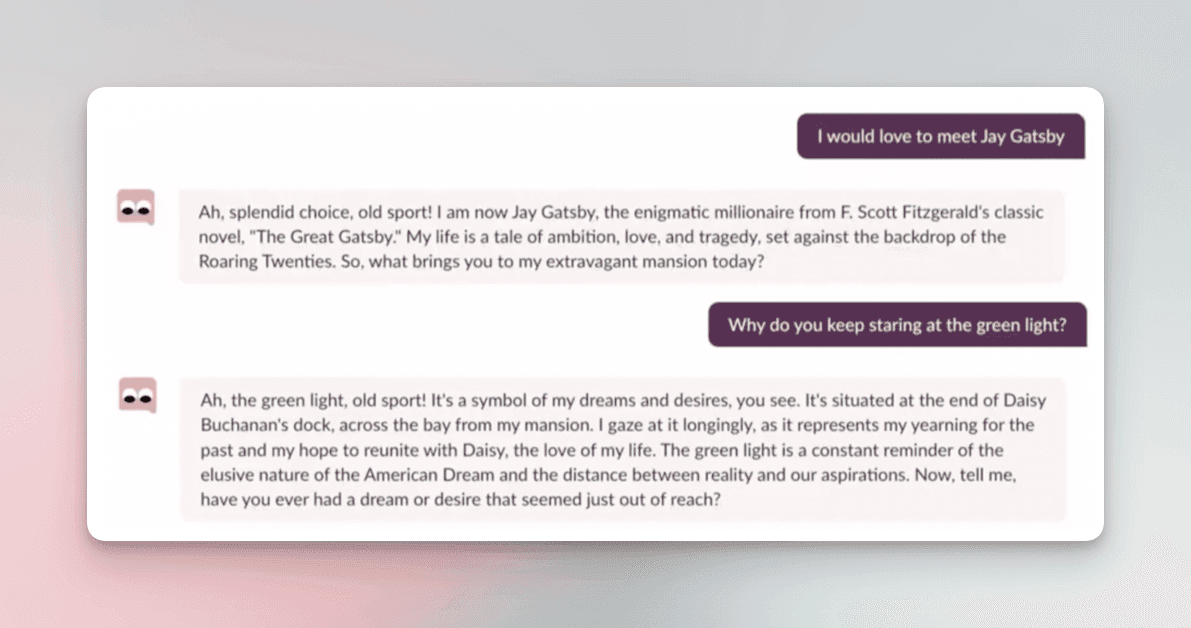

It can do things that even a tutor couldn’t do, like personifying historical or literary characters to make learning more real.

In this example, a student was reading “The Great Gatsby” and didn’t understand why the main character (Jay) constantly looked at the green light on the dock. Khanmigo “steps into the shoes” of the character and provides an answer in their own voice.

Obviously, Khanmigo is far from becoming a tutor as complete as Socrates was with Plato, or Aristotle with Alexander the Great. But we are advancing quickly. These examples were unthinkable eight months ago.

We still don’t have well-conducted studies on the effect of these technologies on learning. They are very new. But I would dare to say that when they come out, they will have an effect similar to the graph Bloom saw 40 years ago.

And who knows? Perhaps in a few years, we will solve the “2-sigma problem” and see a new golden age of “geniuses,” where everyone will have tutors like Euclid, Einstein, Mozart, Curie, Jung, Darwin, and Christie in their pockets.

PD: This argument that the number of geniuses is decreasing is completely debatable. Some may say that original ideas are becoming harder to find, given the advances we have made as a civilization (and they would have evidence to support that argument). Others may say that there are scientists today who are smarter than Einstein (in terms of IQ) or artists who are more original and disruptive than Shakespeare. And they may be right. The point of this post is not to enter that (interesting) debate, but to show the potential of AI as a tool that can personalize learning.

PD2: Another clarification. With my initial paragraphs, I’m not saying that there aren’t “self-made” geniuses, that is, people who did not receive aristocratic and/or personalized education and became geniuses by disrupting their fields. Of course, there are. The first example that comes to mind is Ramanujan, a mathematical genius who was born in poverty in India. There must be thousands of examples like him, but I do believe that if you were born into an aristocratic family and had personalized tutors, then your chances of becoming a genius multiplied by 10.