💪🤖 Why AI Won’t Leave Us Jobless

There’s no place you go where you don’t hear the dreaded phrase “AI is going to replace us all.”

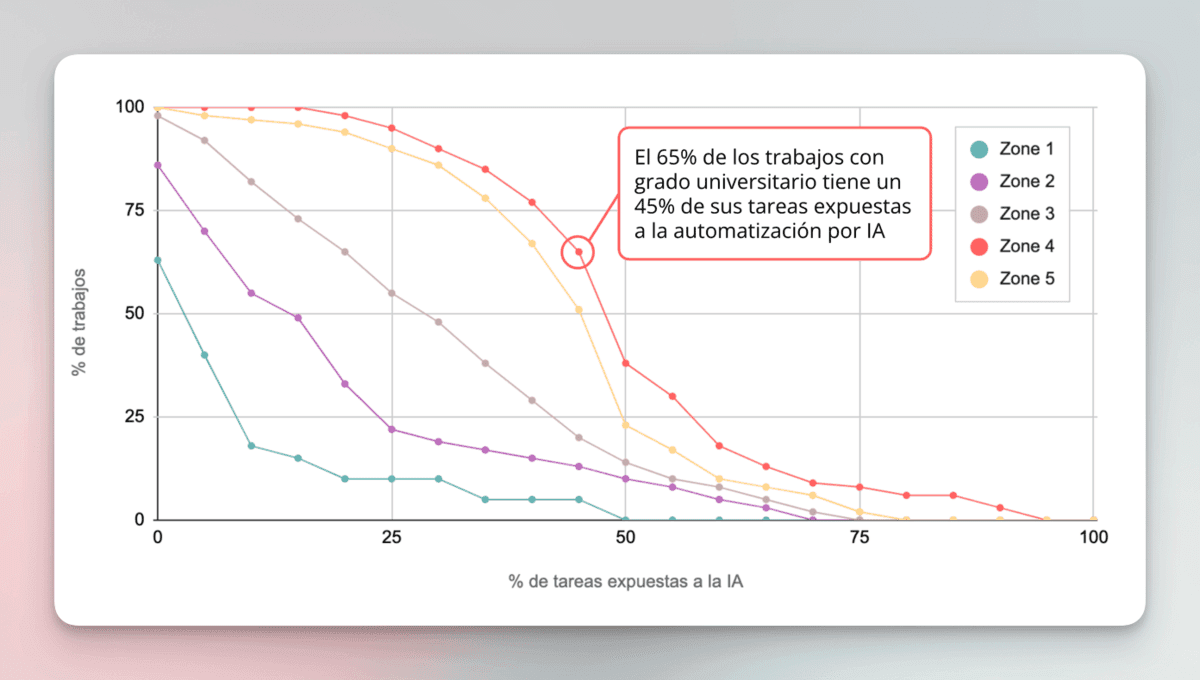

Some studies point in that direction, saying that the productivity improvements these tools bring will have “some level of impact” on 80% of jobs, and a “significant impact” (over 50% of tasks can be done faster with AI) on 19% of the workforce. This McKinsey report talks about 400 million workers worldwide who could lose their jobs due to AI automation.

Here it shows the degree of exposure of 5 types of jobs classified according to the education needed to access them: Zone 1 (no secondary education), Zone 2 (secondary education), Zone 3 (technical education), Zone 4 (university education), and Zone 5 (postgraduate). Each point represents the percentage of jobs (Y-axis) that have that amount of tasks exposed to AI (X-axis). Made

with data I extracted from one of the graphs in the paper by eye, so the numbers may vary a bit.

According to these figures, it seems we are approaching a future where AI leaves us jobless.

But there are two economic principles that make me think exactly the opposite: the adoption of AI in the workplace will generate more demand for “intelligence,” both human and artificial.

Principle 1: Induced Demand

This economic concept occurs when an increase in the supply or capacity of a good, service, or resource leads to an increase in its consumption. More supply generates more demand.

Obviously, this doesn’t happen for all products or services. If tomorrow the supply of toothbrushes multiplied by 10 (if there were 10x more toothbrushes for sale), their demand wouldn’t multiply by 10.

“There are more toothbrushes for sale? Go buy them!” said no one, ever.

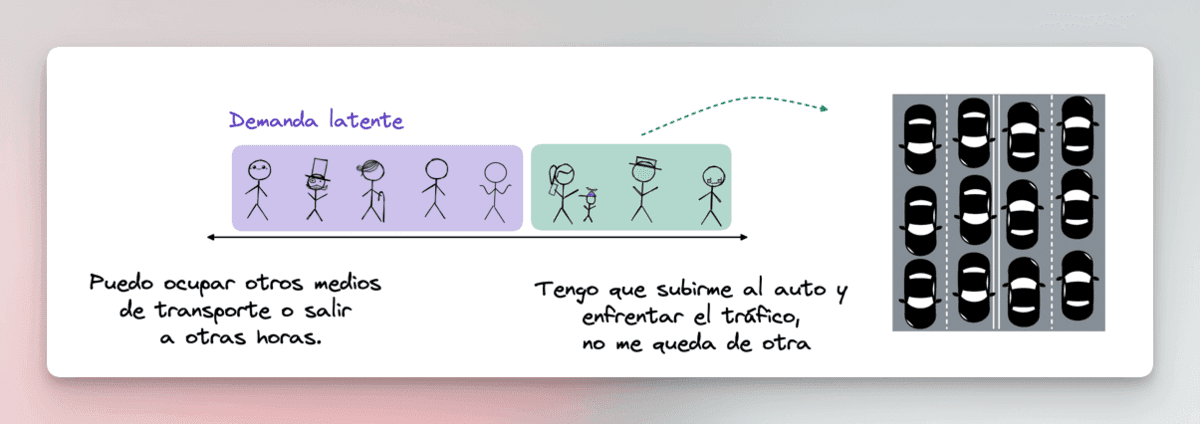

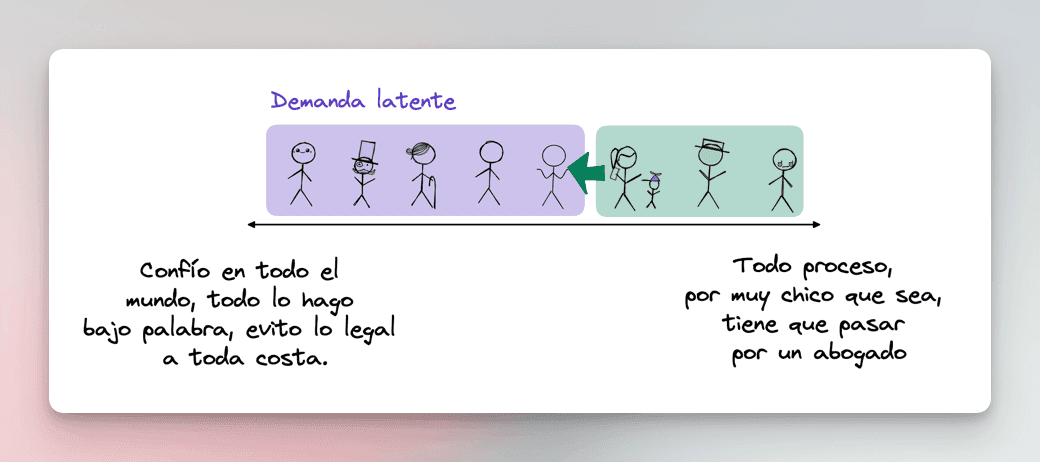

This principle only works when there is latent demand, meaning people are willing to consume more, only if there were more of that product or if it were more accessible.

The classic example is traffic. One would think that the solution to traffic jams is to build more roads. But when you add another lane, the opposite happens.

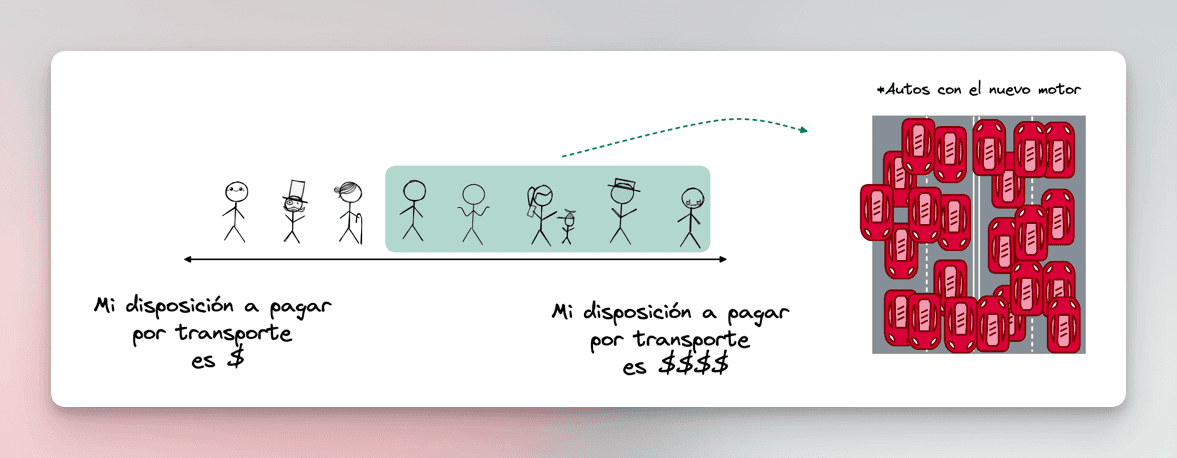

To the question “Do I get in the car in the morning to go to work?”, people are on a spectrum that ranges from “definitely yes, I have no choice but to endure that torture” to “no, I can leave at other times or use other means of transport.”

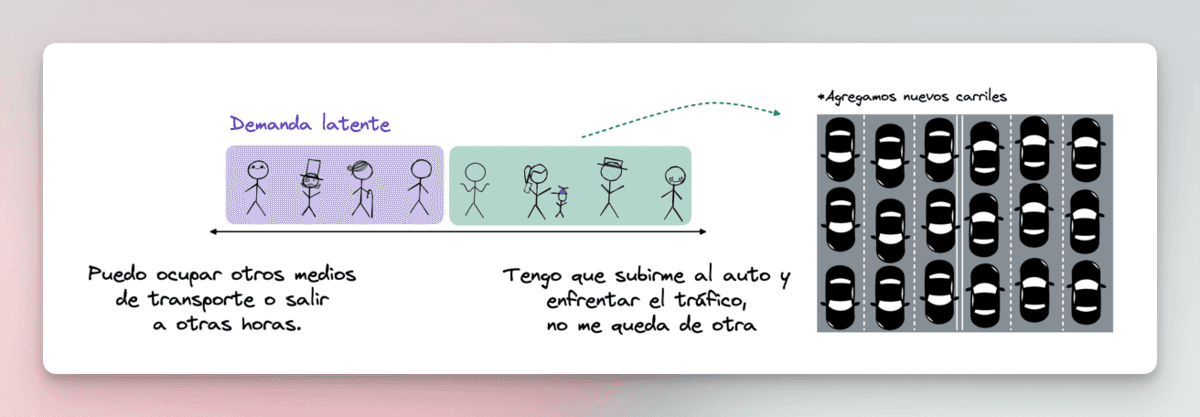

Improving road conditions by adding another lane (increasing its supply) only makes more people willing to move from the purple group to the green group due to that marginal improvement (increasing their demand).

We come back to the same point.

According to this blog post, the latent demand for road space in Los Angeles, USA, is 30x its current capacity. In other words, only 3% of the people who want to travel by car actually do so. The rest find the experience so unpleasant that they prefer not to do it (but they would if conditions improved).

I couldn’t find latent demand figures for LATAM, but if we consider that LA is ranked number 195 in this global traffic ranking, then we can perfectly imagine the situation for Lima (#8 worldwide), Bogotá (#10), Mexico City (#13), São Paulo (#35), and Santiago (#69).

The world record for the longest traffic jam in history goes to the one in the photo. It happened in China in 2010. It was 100km long and lasted 12 days. There were so many people stuck for so long that a mini-economy of selling water at 10 times the price and noodles at four times the price emerged.

Principle 2: Jevons Paradox

There’s another economic concept related to induced demand that can help us understand how demand for “intelligence” will behave in the presence of AI, and that is Jevons Paradox.

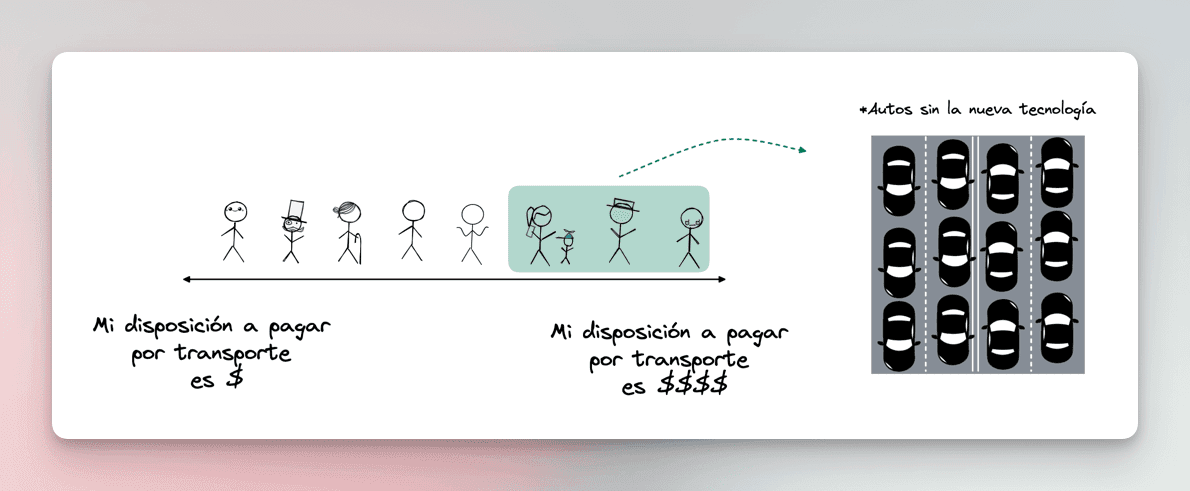

This states that an increase in the efficiency of using a resource does not lead to a decrease in the total consumption of that resource, but rather an increase. This paradox is based on the idea that improving the efficiency of using a resource reduces its cost, which increases its demand.

In our road example, if we don’t increase the lanes, then demand will be largely defined by the overall experience evaluation, which is largely driven by price.

Imagine that a new engine technology is developed that makes cars consume less gasoline per kilometer. This “savings” in gasoline costs will mobilize more people to get in the car, even if the experience remains horrible.

The idea is clear. By the way,

it was ChatGPT who gave me this illustrative example

.

What Does This Have to Do with AI?

If we combine these two principles, we can understand why more “intelligence” will mean an increase in the demand for the total “intelligence” of the system.

Let’s take lawyers as an example.

Nowadays, any legal procedure is expensive and cumbersome. No one wants to voluntarily enter a legal dispute over small matters. If we can skip a contract and do things “by word” (if the level of trust allows), we prefer that route.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t latent demand. There is. It’s just that we prefer not to get into legal troubles unless it’s strictly necessary.

Now imagine that the supply of lawyers multiplies by 10, in the form of AbogadosGPT that can handle the simplest tasks. And also imagine that the efficiency of lawyers improves substantially as they start to rely on AI. Here are the two principles working at the same time. There’s more supply of “lawyers” (induced demand) and there’s an improvement in the efficiency of lawyers (Jevons Paradox).

Result: an increase in the demand for lawyers.

If the price of legal services drops and the process becomes much more convenient, then the number of lawsuits will likely multiply, and contracts for everyday matters will increase. No one wants more lawsuits or contracts, just as no one wants more traffic, but that’s how these principles work in the face of latent demand.

On a more “positive” note, this means that AI probably won’t replace us in the short term. Human nature, always wanting more, will lead us to transform that latent demand into real demand. Jeff Bezos put it best in

his 2017 letter to Amazon shareholders

.

It may be a bit bittersweet to say that the only thing that will keep us employed is our insatiable capacity for consumption. I would love to end this post by saying that the productivity increase led by AI will allow us to have 2 or 3-day work weeks, but that’s probably not the case (I hope I’m wrong!).

In the presence of super-abundance of intelligence, AI won’t take jobs away from lawyers; rather, we will start demanding more from each other.

AI won’t take jobs away from designers; instead, we will start demanding higher quality work in less time.

AI won’t take jobs away from programmers; rather, we will start demanding better custom software.

AI won’t take jobs away from doctors; instead, we will ask about every detail of our health, down to the smallest things.

In summary, AI won’t take our jobs.

PD: This week’s post was a blatant copy of this essay by Patty McKomic. Recommended reading if you want to delve deeper into this topic.